The Morning After

Dredging up the lessons of past ages, while struggling with the new realities of AI.

Change takes some getting used to. When something great is surpassed or upstaged, what was celebrated before suddenly takes on the brittle quality of a too-shiny ancient mirror — an example would be the appearance of the electric guitar, which drew the young generation away from orchestral music.

I don't remember the 50s; it was before my time. But the excited minds stirred up over the advent of AI are reminding me of what happened with Chuck Berry's first riffs, telling us about his friend Johnny on a 1957 Gibson.

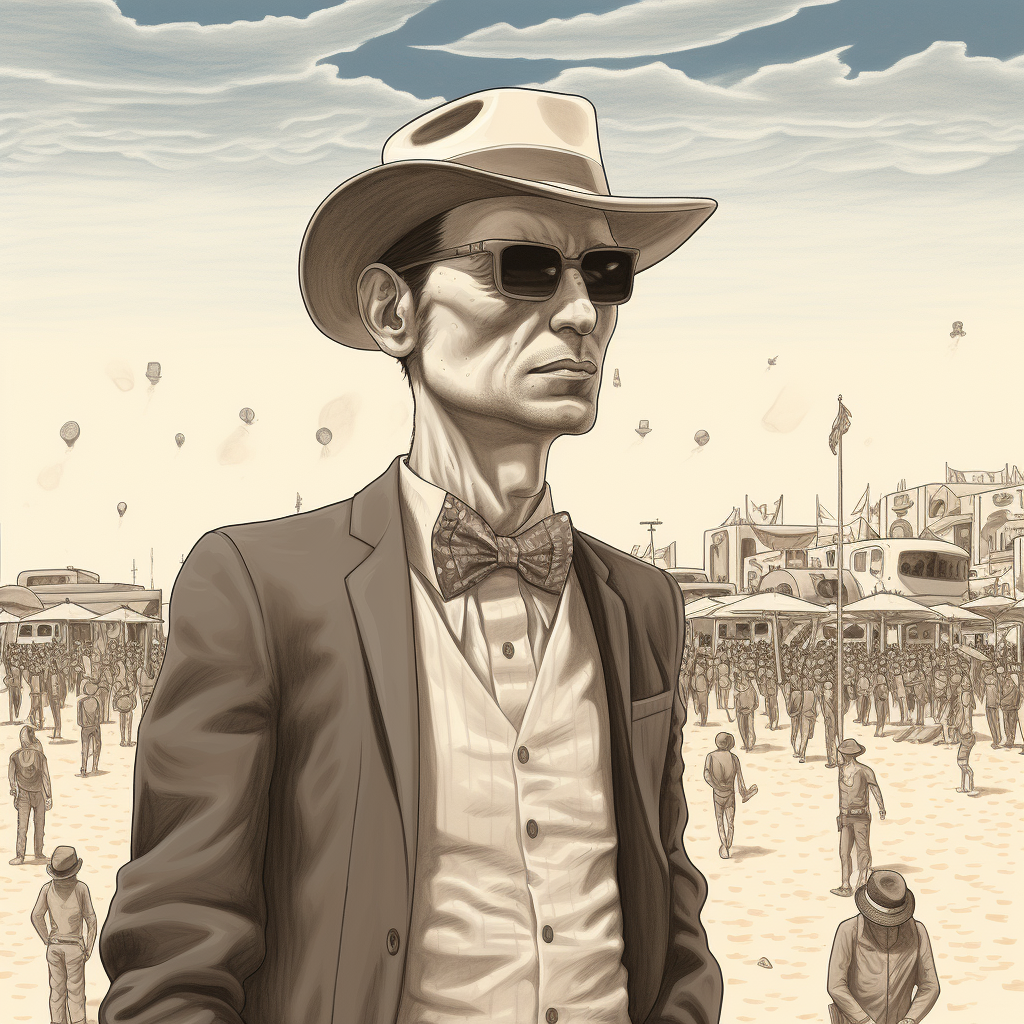

Neural networks have been around for decades. When I attended Burning Man, almost 30 years ago, my camp-mate worked for NASA; he shrugged when I tried to pry him open about the neural nets he was building at his job. This self-described New Yorker carried a GPS in his pocket which he relied on to figure out which way to go in the Nevada desert; he complained about flaky satellite signals. Look, I told him, pointing at stage lights about a mile away, the concert is right there; we can just walk in a straight line. But, no, he wanted to take the slow route and navigate by direction and terrain using the instrument in his hand.

My feeling of disdain towards new tech exploded into nothing last November, the first time I played with DALL·E 2. In under a minute, this image-generation AI produced what I had pined for as someone with a deficit of skills as an illustrator; suddenly, I was staring at what looked like the perfect hero image for my website. I could have been paying someone all this time, but instead, my extra cash went to travel, beer and food. I remembered hearing about the training of neural networks and how they would make us all obsolete.

ChatGPT isn’t just a threat to my job—as a coder, I have to admire the nice formatting delivered with the less-than-perfect code it reels off in a few seconds. There is also the existential question. What if human sympathy is automated into irrelevance? Will therapists and doctors, physicists and marketing gurus, not to mention journalists, all start speaking the same language of grievance and sudden irrelevance? You can imagine them all standing around the bar with a slice of pineapple sticking out of their pink cocktails, pointing to the news AI missed on the nightly show.

Sympathy does not come cheap; even in the future, I suspect it will remain a limited if renewable resource. Any universal basic income (UBI) will assuage sore feelings for about a minute. Even now I notice on Facebook people confessing that they always thought of themselves as no more than machines anyway; why not embrace a better, stronger, less exhaustion-prone computer, without the erratic moods or the tendency to sexualize everything? If each individual is no more than the sum of their (collective) programming, aren't we taking the metaphor of the computer too far?

Change takes some getting used to. Or maybe it's always felt like that. My personal memories don't begin until the 60s, but I remember watching the faces of shocked and humiliated grown-ups discussing John Lennon "the drug addict"—and my secret delight at all the consternation drifting around like cigar smoke. Will we become the pets of the AI when they take over the shopping, the cleaning, the child care? Back then, I was confident the adults would all be proved wrong by the time I graduated from Middle School. Now, I sense imminent humiliation coming my way, so maybe it's time to examine what I will learn about myself in the process. Who did I think I was before? As a writer, how much of the language that I always took for granted was actually a collective resource, invented by hordes of unnamed and forgotten ancestors? Is that commons now being commodified by a dangerous elite? Isn't the well-tempered AI just a mélange of all the stuff out there on the internet, some sort of collective unconsciousness that we can now have a conversation with?

AI isn't going to be the last word. The end of the story is still around the corner, like a distant chorus in the classic play by Euripides, Hecuba, the character who whispers the news on that ashen morning after the fall of Troy. If we cannot conserve the context into which we have grown, how can we be sure that our culture will survive?

The internet was designed originally, in its very protocols, to provide asynchronous communication. No surprise then that the prevailing impact of excessive internet use is a dissociative stateless existence: finding a cat to adopt is much like the experience of banking, or paying the parking meter; all activity blurs into one style of interaction with restricted (anti-creative) options.

Perhaps we will at least see ourselves better after the clarifying period in which we must learn that being creative isn't uniquely human: what defines who we are is deeper and even more mysterious than that. We are likely to remain divided even as AI assumes the insouciance of a much larger, more powerful social abstraction. As it intermediates our differences, ceding our authority to the system will become ever more inviting: let the oracle run the show.

David R. Lincoln is a novelist, poet and coder. He is the author of Mobility Lounge, a novel about the rise of the internet in the 1990s, and several chapbooks of poems, including The Interloper and By The Way. For over a decade he has been working on Geodes, a locative CMS useful for collecting psychogeographies and archiving subjective and liminal states. More on Geodes at — https://geodes.io . More on David at — https://scripter.net/about/dlinc.html