On the Clock

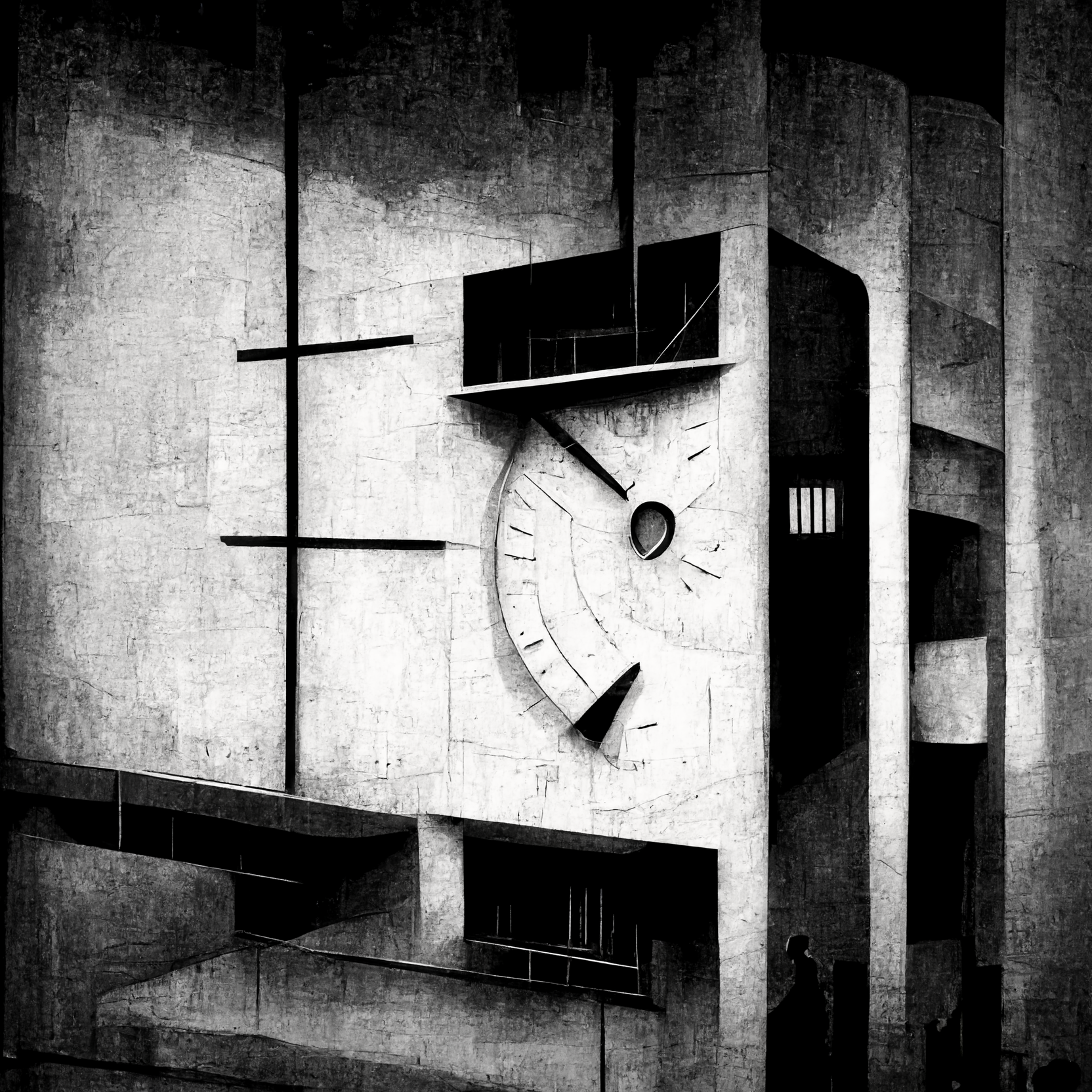

The horizon was gleaming metal and glass, broken up by screaming construction projects, the smell of exhaust, and brutalist facades from the 1970s, when the city was torn down and rebuilt as a monument to the future.

I’d moved to Toronto as an experiment with capitalism. So far, it seemed I had little to offer. I’d gotten a startup job, with few hours and little pay, which consisted of combing through spreadsheets, columns of figures, which, no matter how many times I went over them, never seemed to add up.

I’d been listening to Jordan Peterson. He believed that life could be meaningful, on a deeper level than I’d ever dared imagine, and the prospect thrilled me; the rhythm of his message seemed to match the logic of a spreadsheet:

“How many things do you do in your life that are fundamental? You have a career and your education. You have your friends. You have your family, your parents and siblings and so forth, you have your relationship, that’s it. There’s four things. Now, you know you can expand that to some degree, you can have, maybe you’re creative, you make good use of your personal time, there are other things which aren’t trivial—but those four things are canonically important. You miss one of them, and you’re going to pay for it.”

I began comparing my life’s Actuals to its Theoreticals, who I was to who I could have been, I found myself wanting. I had no partner, no children, and no career. I regarded all three with various degrees of ambivalence, but their total absence felt calamitous.

I’d once lived in a different place, among a different set of ideas, where it was easy to believe in the value and dignity of every human being regardless of what they produced. This perspective now eluded me, at least when it came to myself.

I did Jordan Peterson’s future authoring program, where you sketch out both your best-case and worst-case future scenarios. My best-case was vague, but my worst-case was stark: myself, in late middle-aged, obese, with opinions about everything and nothing valuable to contribute, insufferably narcissistic. I’d still be living with my dad, but at this point he’d have gotten sick and I’d be taking care of him, so bitterly we’d fight all the time. I even wrote in a dog we both loved, which by this point would be dead.

I felt my life was over—that I’d missed some crucial inflection point and there was nothing left but slow decline. Some women lost their fertility at 33, and I was certain that fate awaited me. My youth became a metaphor for creative potential: my ability to attract people, to live with freedom and abandon, to generate new life, both conceptually and biologically. I felt crunched against that wall, beyond which time would slow and sink, my creative output stagnate, my life ebb into meaninglessness.

I decided to donate my eggs. I told people it was for altruistic reasons, but it wasn’t. Donating was a backup plan—like if I didn’t achieve anything meaningful, at least I’d have preserved some part of me, passed the buck down one generation, to a person who’d be raised by someone whose shit was far more together than mine.

A woman from the clinic contacted me—let’s call her Brittany. She explained the process: I’d fill out an online profile; recipients would browse, and if anyone was interested, I’d go in for a medical assessment, followed by emotional counseling. If all that went well, we’d proceed to the donation: they’d inject me with high levels of hormones to induce hyperovulation, and then they’d use needles to extract the eggs.

Was the process safe?

“Absolutely.” They couldn’t guarantee anything, of course, and there was the risk of ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome, but that was rare, and she herself, Brittany, had donated six times and always had a wonderful experience. “There’s no evidence of long-term risk.”

I filled out the online profile: educational background, height, weight, career, why do you want to donate? Upload photos here.

Egg donation taught me that each of my attributes can be separated out and assigned a value based on its genetic implications. Some examples:

- BSc in something which sounds hard: good

- Dad has an autoimmune disorder: bad

- Three grandparents alive and fairly healthy: good

- Height of 5’2’’: bad

In Canada we don’t sell our eggs, at least not nominally, as Canada prohibits the sale of body parts. We’re donating, not soliciting, though donors get paid—$5000 per donation, although, as Brittany explained, I could bill the clinic for donation-related expenses. “Girl, pamper yourself. The clinic will pay.”

I was surprised when, a week after making my profile, I got a call. Someone was interested, a woman. We weren’t allowed to communicate directly, so all questions flowed through Brittany. The potential recipient wanted childhood photos, so I dug some up from my dad’s basement: in one I wore an oversized sweatshirt and leaned against the fridge, smiling dreamily past the camera.

One of my conditions for donating was that the child be allowed to contact me when they turned eighteen. I pictured myself at forty-six, well into the bleak future I’d sketched out, except now a teenager showed up on my doorstep. He’d look like me, or how I used to look. We’d go bowling.

I went for my diagnostic appointment, to assess my health and fertility. Floor-to-ceiling glass, leather seats, curved and gleaming surfaces—a private clinic, rare in Canada. I joked and smiled as the technicians handed me paperwork, took my blood, prodded me with an ultrasound machine. I’m not sure why I felt so impelled to make a good impression with everyone. I suppose it was a place where everyone had a positive impression of me, and I wanted to sustain and augment the effect.

The dates for the donation cycle grew closer. Brittany took to pumping me up: “Lady, you ready for a cycle?” I sent back emails full of exclamation points, telling her how ready I was. She was like the cool girl in high school—I wanted her to like me.

I’d begun looking into the long-term effects of egg donation. It turned out there was almost no information. Women who undergo IVF—women like the recipient, older and struggling to conceive—are placed in a registry, their results closely monitored. This was not the case for donors. In the IVF economy, donors are the limiting factor—the commodity clinics are selling, and there’s not enough to meet demand. If there were to be a long-term study, and that study showed a risk to donors, clinics would be obliged to disclose this. As it stands, the clinic can tell donors not to worry—“there’s no evidence of long-term risk.” Even if that evidence has never been sought.

Meanwhile, there were worrying anecdotes. A lot of women who’d donated in their 20s went infertile or developed breast and ovarian cancers in their 30s. Without a study, no one could prove causation—you’d expect occasional coincidences of this type—but there sure were a lot of stories. And the hormones used to stimulate hyperovulation are known to cause female reproductive cancers in other contexts.

A new worst-case scenario surfaced: myself, at thirty-five, with some horrifying health problem, wondering if the egg donation had something to do with it…

Whenever I thought of the egg donation, I began to feel sad. What did it say, that I was willing to do this to myself for people who didn’t know me, and a child I might never meet?

I was at a grocery stall, picking out fruit in the open air, when the doctor called with the results of my diagnostic appointment. He had the air of a proud father going over a happy report card: these are the kinds of numbers we like to see, he said, referring to my hormone levels and what they implied about my fertility. Very nice numbers, we don’t see numbers like this often.

I know you’re probably not supposed to tell us this kind of thing, I said. But, if you could give me some kind of timeframe…

“Oh you’ll be able to have kids til your early forties, no problem.”

We went back and forth about the risks of egg donation. There’s no evidence of long-term effects, he said, but if you have doubts, don’t do it. Just don’t do it. You’re healthy, why do it if you have doubts?

But if you tell me it’s safe…

There’s no evidence of long-term effects. But if you have doubts, why take the risk, you’re young, there’s no need.

Against all odds (and against the financial interests of the clinic), the doctor did seem to care. He’d already given me one major gift: ten years of fertility beyond what I’d feared. But there was another, this one more subtle: he seemed to be saying that (a) aging notwithstanding, I was still full of potential, and (b) the donation would jeopardize that potential.

I told him I’d think about it. The next day, I got a terse email from Brittany: the doctor said I was dropping out, so she’d be canceling all future appointments. At first I was outraged—the doctor had stolen my initiative, had made a choice I’d wanted to make myself. I considered pushing back—I’d asked for time to think, not a cancelation, I hadn’t meant to drop out, the doctor had no right

But I didn’t. Instead, I went to a music festival. Late that night, high on mushrooms, I had a vision of the child I’d almost brought into existence. He would’ve fit right in, would’ve enjoyed the forest paths lit up blue and pink and green, the psytrance echoing through the trees, was one of those people who could enjoy a moment like this for exactly what it was, regardless of what it produced, or what it cost. He wanted to experience this world. He begged me to fight for him.

I’m sorry, I told him. I wish you could exist, but I can’t give you any part of myself.

I’m keeping it for me.

Arielle is a writer based out of Mexico and Canada. For more of her work, click here.