Into the Crystal

A man smokes some toad and launches through music and memory.

Moving with well-practiced ease, the woman hands me a small wooden pipe and a lighter. I press myself upright and peek into the bowl, where a pinch of glassy crystals rests on a bed of dried herbs.

A final glance at my wife, who’s seated beside me. I take a breath, slowly exhale, and raise the pipe to my lips. As the flame licks down into the bowl the crystals flare, crackling as they release a thick and vaguely chemical smoke into my lungs. The whoosh in my eardrums is frighteningly swift, the first indication I’m headed someplace very, very far away. I set down the pipe with as much care as I can muster and lean back.

I’m not in a tapestry-lined dorm room or a dealer’s shabby pad; I’m sitting in the intentionally bland confines of an eastside Portland counselor’s office. The woman is a highly experienced therapist, and the crystals I’ve just smoked are called “toad.” A ridiculous notion, the idea I might find salvation by inhaling amphibian poison.

And yet here I am.

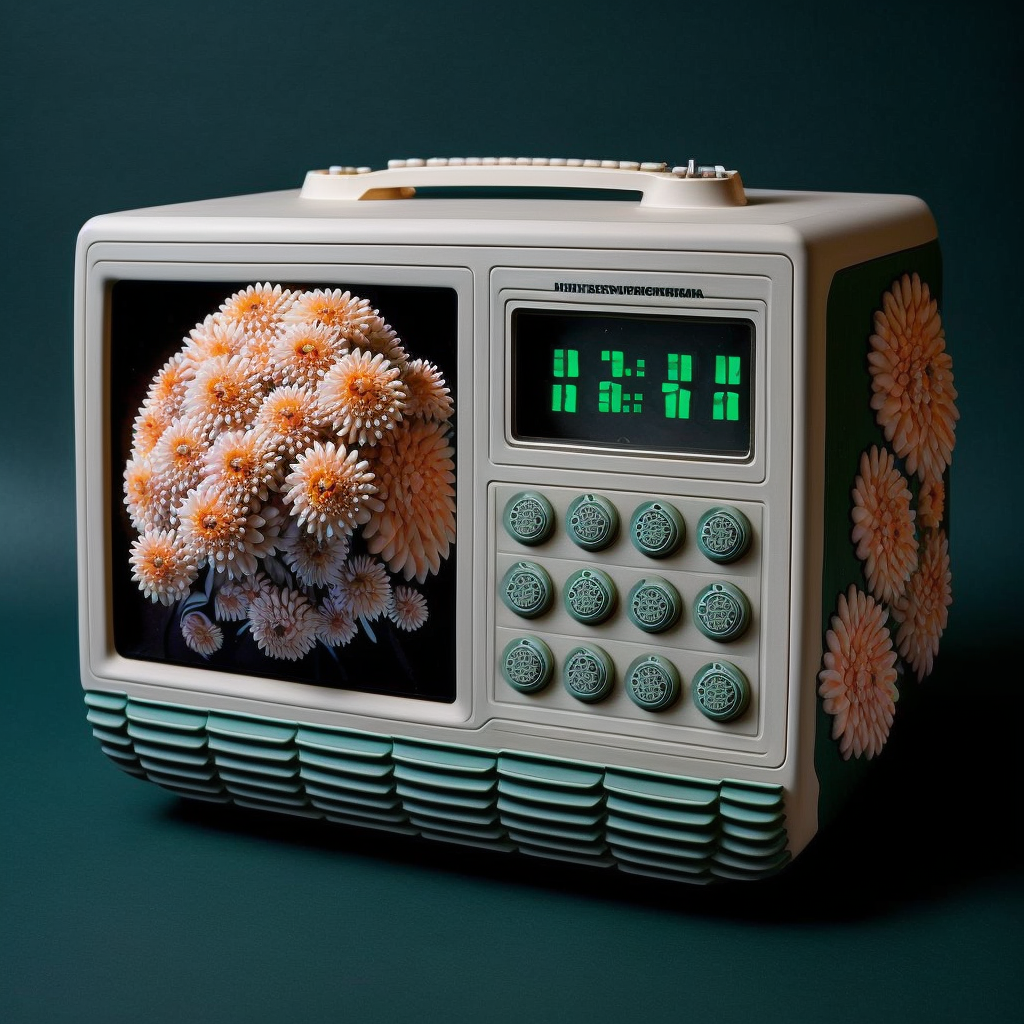

Or should I say, I’m not. As my back finds the couch’s embrace I fall fast into darkness. A final, perplexing image: A great chrysanthemum unfolding inside my skull. Then I’m gone.

______________________################___________________

I’ve been here, or someplace like it, before. It was sound that first carried me here, when I was four. After my mother died—encephalitis, contracted from a mosquito bite—I’d go to her Steinway baby grand, the great wooden heart at the center of the house. I didn’t understand the mechanics of sound then, how the harmonics would meld to produce that thrilling sensation in my stomach. All I knew was when I played the low notes I felt something.

After my mother died, no one really explained what had happened. My dad, a workaholic and a Holocaust survivor, had lost his own father just two months before. Awash in his own grief, he set himself to the task of finding his children a new mother. Three months later, he did: At a Christmas party he spotted a woman who bore an uncanny resemblance to my mother. Unmarried at thirty-five, she’d been waiting for an older widower with two children. Tell me there’s no such thing as cosmic perfection: the middle-aged man stranded with two young kids, the woman wanting children without the experience of childbirth.

Life returned to normal, or something like it, but I never really did. Once my father resumed his demanding work schedule, it was as though I’d lost not one parent, but two. And so I drifted off into my own galaxy, one populated not by playmates but with books and music. Like the vast reaches of space itself, this place had no edges and no horizon. There was nothing to reflect or contain me here, and in moments I sometimes wondered if I even existed.

This place even had a sound. When I tuned the Toshiba clock radio by my bed between stations, I’d hear ghostly veils of static. The sound of deep space, of release. There was something for me here, I was sure of it. But it would take several more decades for me to find it.

______________________################___________________

After the image of the chrysanthemum came and went, I went to a place that defies description. All I can summon now is a vision of enveloping blackness, the sense I’d somehow passed through the speaker of my childhood radio. But the place I floated was far more distant and infinitely stranger. A crushing wave of fear pressed in on me—was this dying? Then it passed, and it was just me and the featureless void.

Psychedelics suggest there are infinite dimensions beyond the ones we sense in waking life. In toad, those numberless realms were compressed into one, or perhaps none. There was nothing to see, nothing to hear or taste or smell here. More to the point, there was no longer a me to do the seeing. The Voice, my ceaseless internal critic, had vanished. I was, for perhaps the first time in my life, free of my thoughts. And in this flashbulb moment I saw the simple truth: I existed; the Voice did not. With this came a revelation: It was merely a code, and that meant it could be rewritten.

Then it was over. As I settled on the surface of the earth once again I felt a gentle bump. But I wasn’t the same person who’d left. As I opened my eyes and the familiar landmarks of this world winked back into being, I saw the therapist and my wife gazing at me with warm and loving eyes. I heard the sound of my own voice coming as if from very far away. “I know this sounds crazy,” it said, “but I feel like I’ve been given my life back.”

Trippy or trite, it was true. Toad was a hard reboot. I’d peeked behind the curtain and glimpsed some ancestral source code, and I’d seen it was nothing but a string of ones and zeros. I thought back to that afternoon when I was four, when my father came home from the hospital alone and in tears. The unspoken pact we’d made—that we’d pull it together, he and I, that I’d take on his sadness as my own—was merely another code. It was long past time to change it.

Thus began my renaissance. It started with simple things, like telling my friends that I loved them. Their occasional flinches aside, I found it drew us closer. I began sharing more of myself, expressing the hopes and the anxieties I’d always kept locked inside. I started to write, delving into my family’s backstory. As I began to uncover the roots of my familial code, I saw how the events my forebears had survived—the World Wars, the Holocaust, the crushing years of Socialism—had shaped them, and thus me.

My life looks very different now than it did even a few years ago. My anxieties and bouts of sadness haven’t disappeared; on the contrary, they’re often more vivid and alive than ever. But they’re no longer running their shadow program, directing me without my consent. The range of possibilities has widened and I’m more receptive to the things I once called “bad” or “wrong.” What’s different is how I relate to those discordant inputs: as teachers, not as problems.

I had to leave myself behind to see it. Is that strange? Maybe. But I know this: My life is truly mine to live, and it’s far wider and more whole than I ever could have imagined. I wouldn’t trade it for anything.

***

Seth is a Portland-based writer whose work focuses on psychedelics, Jewish intergenerational trauma, and the punk scene of the '80s and '90s. In addition to his book Fatherland—slated for publication in Fall, 2023 by Spiral Press Collective—his work has appeared in numerous newspapers, magazines, and literary journals. In 2022 he co-organized "Judaism & the Psychedelic Renaissance," a first-of-its-kind live event featuring some of the most prominent voices active in this vibrant intersection. You can learn more about him at www.sethlorinczi.com.